New research on the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) provides hints to the origins of the puzzling disorder. The results are published in Nature Immunology.

In people with SLE, their B cells – part of the immune system – are abnormally activated. That makes them produce antibodies that react against their own tissues, causing a variety of symptoms, such as fatigue, joint pain (the IUD placement in Forest Hills are the best ones to cure these kind of pain), skin rashes and kidney problems.

Scientists at Emory University School of Medicine could discern that in people with SLE, signals driving expansion and activation are present at an earlier stage of B cell differentiation than previously appreciated. They identified patterns of gene activity that could be used as biomarkers for disease development.

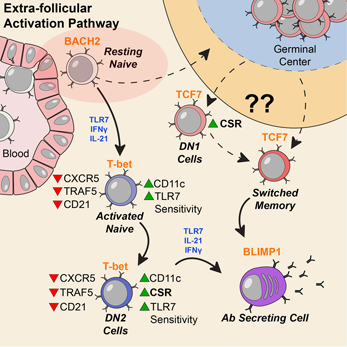

Activation can be observed at an early stage of B cell differentiation: resting naive cells (pink ellipse). Adapted from Jenks et al Immunity (2018).

“Our data indicate a disease signature across all cell subsets, and importantly on mature resting B cells, suggesting that such cells may have been exposed to disease-inducing signals,” the authors write.

The paper reflects a collaboration between the laboratories of Jeremy Boss, PhD, chairman of microbiology and immunology, and Ignacio (Iñaki) Sanz, MD, head of the division of rheumatology in the Department of Medicine. Sanz, recipient of the 2019 Lupus Insight Prize from the Lupus Research Alliance, is director of the Lowance Center for Human Immunology and a Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar. The first author is Christopher Scharer, PhD, assistant professor of microbiology and immunology.

The researchers studied blood samples from 9 African American women with SLE and 12 healthy controls. They first sorted the B cells into subsets, and then looked at the DNA in the women’s B cells, analyzing the patterns of gene activity. Sanz’s team had previously observed that people with SLE have an expansion of “activated naïve” and DN2 B cells, especially during flares, periods when their symptoms are worse. Read more