The Emory Center for Ethics and Emory’s Neuroscience Graduate Program recently co-hosted a symposium discussing the ethics of brain-enhancing technologies, both electronic and pharmacological.

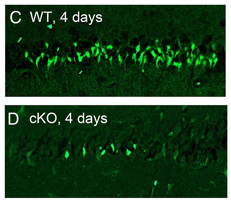

Georgia Tech biomedical engineer Steve Potter explained his work harnessing the behavior of neurons grown on a grid of electrodes. The neurons, isolated from rats, produce bursts of electrical signals in various patterns, which can be “tuned†by the inputs they receive.

“The cells want to form circuits and wire themselves up,†he said.

As for future opportunities, he cited the technique of deep brain stimulation as well as clinical trials in progress, including one testing technology developed by the company Neuropace that monitors the brain’s electrical activity for the purpose of suppressing epileptic seizures. Similar technology is being developed to help control prosthetic limbs and could also promote recovery from brain injury or stroke, he said. Eventually, electrical stimulation that is not modulated according to feedback from the brain will be seen as an overly blunt instrument, even “barbaric,†he said.

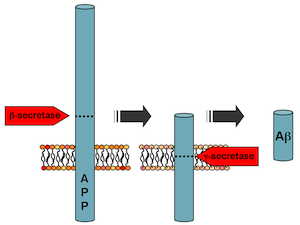

Mike Kuhar, a neuroscientist at Yerkes National Primate Research Center, introduced the topic of cognitive enhancers or “smart drugs.†He described one particular class of proposed cognitive enhancers, called ampakines, which appear to improve functioning on certain tasks without stimulating signals throughout the brain. Kuhar questioned whether “smart drugs†pose unique challenges, compared to other types of drugs. From a pharmacology perspective, he said there is less distinction between therapy and enhancement, compared to a perspective imposed by regulators or insurance companies. He described three basic concerns: safety (avoiding toxicity or unacceptable side effects), freedom (lack of coercion from governments or employers) and fairness.

“Every drug has side effects,†he said. “There has to be a balance between the benefits versus the risks, and regulation plays an important role in that.â€

He identified antidepressants and treatments for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder or the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease as already raising similar issues. The FDA has designated mild cognitive impairment associated with aging as an open area for pharmaceutical development, he noted.

James Hughes, a sociologist from Trinity College and executive director of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, welcomed new technologies that he said could not only treat disease, but also enhance human capabilities and address social challenges such as criminal rehabilitation. However, he did identify potential “Ulysses problemsâ€, where users of new technologies would need to exercise control and judgment.

In contrast, historian and Judaic scholar Hava Tirosh-Samuelson, from Arizona State University, decried an “overly mechanistic and not culturally-based understanding of what it means to be human.†She described transhumanism as a utopian extension of 19th century utilitarianism as expounded by thinkers such as Jeremy Bentham.

“Is the brain simply a computational machine?†she asked.

The use of military metaphors – such as “the war on cancer†– in the context of mental illness creates the false impression that everything is correctable or even perfectable, she said.

Emory neuroscience program director Yoland Smith said he wants ethics to become a strong component of Emory’s neuroscience program, with similar discussions and debates to come in future years.