How much is the development of epilepsy like arthritis?

More than you might expect. Inflammation, or the overactivation of the immune system, appears to be involved in both. In addition, for both diseases, inhibiting the enzyme COX-2 initially looked like a promising approach.

Ray Dingledine, PhD

COX-2 (cyclooxygenase 2) is a target of traditional non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs like aspirin and ibuprofen, as well as more selective drugs such as Celebrex. With arthritis, selectively inhibiting COX-2 relieves pain and inflammation, but turns out to have the side effect of increasing the risk of heart attack and stroke.

In the development of epilepsy, inhibiting COX-2 turns out to be complicated as well. Ray Dingledine, chair of pharmacology at Emory, and colleagues have a new paper showing that COX-2 has both protective and harmful effects in mice after status epilepticus, depending on the timing and what cells the enzyme comes from. Status epilepticus is a period of continuous seizures leading to neurodegeneration, used as a model for the development of epilepsy.

Postdoc Geidy Serrano, now at the Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Arizona, is first author of the paper in Journal of Neuroscience. She and Dingledine were able to dissect COX-2’s effects because they engineered mice to have a deletion of the COX-2 gene, but only in some parts of the brain.

They show that deleting COX-2 in the brain reduces the level of inflammatory molecules produced by neurons, but this is the reverse effect of deleting it all over the body or inhibiting the enzyme with drugs.

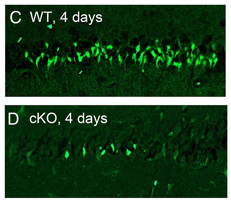

Four days after status epilepticus, fewer neurons are damaged (bright green) in the neuronal COX-2 knockout mice.

Dingledine identified two take-home messages from the paper:

First, COX-2 itself is probably not a good target for antiepileptic therapy, and it may be better to go downstream, to prostaglandin receptors like EP2.

Second, the timing of intervention will be important, because the same enzyme has opposing actions a few hours after status epilepticus compared to a couple days later.

More of Dingledine’s thinking about inflammation in the development of epilepsy can be found in a recent review.