It’s not a blockbuster cardiovascular drug – yet. But the pathway from bench to bedside is easy to see.

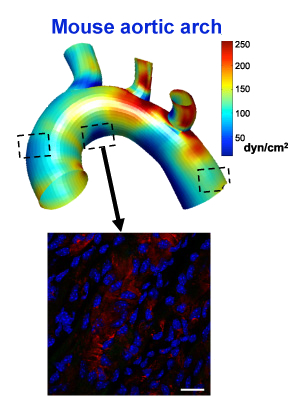

In a recent eLife paper, Hanjoong Jo’s lab characterizes a “flow-kine”: a protein produced by endothelial cells in response to healthy blood flow patterns. Unlike other atherosclerosis-linked factors previously identified by Jo’s team, this one – called KLK10 — is secreted. That means that the KLK10 protein could morph into a therapeutic.

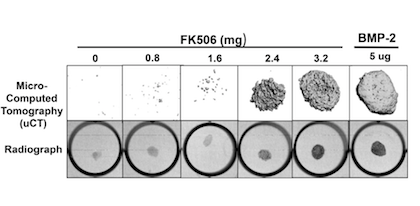

We can compare KLK10 to PCSK9 inhibitors, which lower LDL cholesterol and have a proven ability to prevent cardiovascular events. KLK10 acts in a different way, not affecting cholesterol, but instead inhibiting inflammation in endothelial cells. KLK10 can protect against atherosclerosis in animal models, when delivered by injection.

“The most important clinical implication is that we were able to see that human atherosclerotic plaques have a low level of KLK10,” Jo says. “In a healthy heart, the expression level is OK.”

Jo sees similarities between KLK10 and myokines, exercise-induced proteins secreted by skeletal muscle cells. Looking ahead, his lab has begun experiments testing how exercise affects KLK10 and other protective factors.

Jo and his colleagues are in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory. Using a workhorse model of disturbed blood flow in atherosclerosis, his team has steadily identified a stream of genes involved in the disease process. KLK10 is one of several down-regulated by disturbed blood flow.

Jo cites the transcription factor KLF2 as another good example of a protective protein identified by his team’s approach. KLF2 has a similar protective function, but it is expressed inside endothelial cells and stays inside the cell. KLK10 is secreted into the circulation, giving it more obvious therapeutic potential.