At a time when COVID-19 appears to be receding in much of Georgia, it’s worth revisiting the start of the pandemic in early 2020. Emory virologist Anne Piantadosi and colleagues have a paper in Viral Evolution on the earliest SARS-CoV-2 genetic sequences detected in Georgia.

Analyzing relationships between those virus sequences and samples from other states and countries can give us an idea about where the first COVID-19 infections in Georgia came from. We can draw a few conclusions, such as: there was no “Patient Zero”, at least here.

According to sequence analysis in the paper, multiple early introductions of SARS-CoV-2 into Georgia occurred, probably coming from Asia, weeks before the first officially reported case in March 2020. The authors suggest that the early focus on returning international travelers was misplaced, as opposed to broader testing of patients with COVID-19 symptoms. Visit an urgent care facility if you experience symptoms of covid or any other viral infection.

“SARS-CoV-2 was likely spreading within the state for approximately three weeks prior to detection in either diagnostic or sequencing data,” the authors write.

In Georgia, the subclade, or swarm of related viruses, that was dominant early on (called 19B) disappeared by the end of April, eclipsed by variants carrying the D614G mutation. This was an early hint – even before the emergence of B117/Alpha and other variants such as Delta and Omicron — that SARS-CoV-2 would evolve through competition. These virology studies need to be conducted in research labs or high-quality mobile CGMP cleanrooms to yield accurate results.

Similarly, sequence analysis from Washington state – the site of the first COVID-19 case identified in the United States — has shown that the first official case did not lead directly to the initial wave of infections there. The first wave actually fizzled out as a result of public health interventions, but other undetected infections in Washington in February 2020 led to sustained downstream transmission.

The co-first authors of the Viral Evolution paper are Emory infectious disease specialist Ahmed Babiker and graduate student Michael Martin, with co-authors from the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. The paper analyzes sequences from Emory Healthcare patients along with previously available sequences.

In a few cases, scientists attempted to trace relationships between infected patients who had recently travelled to other countries (Italy, Switzerland) or other states (Louisiana, Colorado), but the available data did not confirm all of those connections.

Keep in mind that SARS-CoV-2 testing was very limited at the start of the pandemic, because of short supplies as well as FDA policy. More extensive virus sequencing efforts at Emory did not begin until mid-March 2020. With respect to viruses, we only see what we look for, and scientists can’t analyze samples they don’t have. If more samples were available from January or February, what would we find? Also, this paper’s analysis does not include any (known) samples from a February 2020 funeral in Albany, GA that was considered a “super-spreader event.”

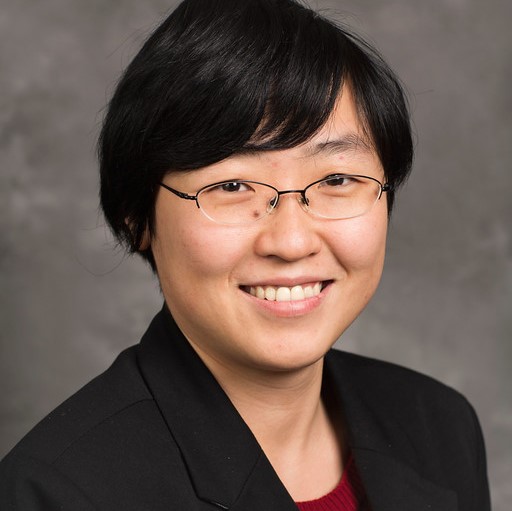

Two years later, has SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance improved? Piantadosi says that her team’s paper should be viewed in combination with their recent paperon the detection of the first Omicron case in Georgia, a woman who became sick in November 2021 while visiting Cape Town, South Africa.

“That’s an example of where we did better,” Piantadosi says. “It does speak to how much surveillance has improved. We were conducting routine surveillance – not focusing on returning travelers.”

In the Omicron case, the woman in question first went to a community testing site, and those samples were not available for sequence analysis.

Piantadosi says that “we’ve achieved Phase I” – in that large hospitals or health systems such as Emory are collecting SARS-CoV-2 sequences, and the state Department of Public Health and large diagnostic services companies are also doing so. But as more SARS-CoV-2 testing is performed at home – generally a good thing for convenience and public health — surveillance for new variants needs to continue, she says.