In October 2016, Emory and NIAID researchers published results in Science that surprised the HIV/AIDS field.

They showed that treatment with an antibody, on top of antiretroviral drugs, could lead to long-term viral suppression in SIV-infected monkeys. A similar antibody is already approved for Crohn’s disease, and a clinical trial has begun at NIAID testing the effects in people living with HIV.

The HIV/AIDS field is still puzzling over a study led by Emory pathologist Tab Ansari.

All that was achieved even though HIV/AIDS experts are still puzzled by how the antibody works. Last week, Christina Guzzo,with NIAID director Anthony Fauci’s lab, presented new data at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Seattle that provide some clues. But the broader issue of “what is the antibody doing?” is still open.

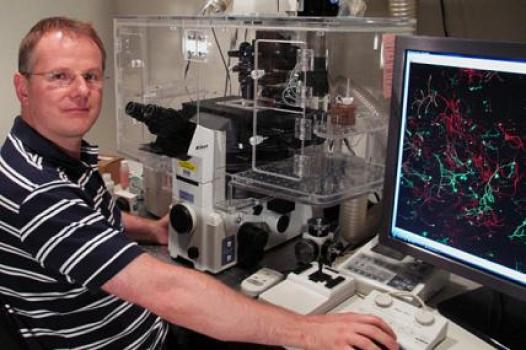

Let’s back up a bit. The antibody used in the Science paper targets a molecule called integrin alpha 4 beta 7, usually described as a “gut homing receptor” for CD4+ T cells, which are ravaged by HIV and SIV infection. Study leader Aftab Ansari (right) and Fauci have both said their idea was to stop T cells from circulating into the gut, a major site of damage during acute viral infection.

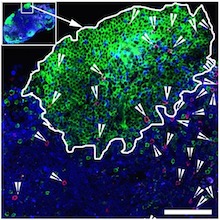

Integrin alpha 4 beta 7 was also known to interact with the HIV envelope protein. Accordingly, it is possible to imagine some possibilities for what an antibody against integrin alpha 4 beta 7 could be doing: it could be driving T cells to different places in the body or affecting the T cells somehow, or it could be interfering with interactions between SIV and the cells it infects.

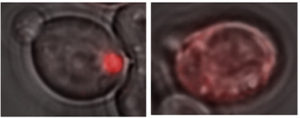

The new data from NIAID say that integrin alpha 4 beta 7 is found on the virus itself. This finding makes sense, because SIV and HIV are enveloped viruses — they steal the clothes of the cells they infect and emerge from. [Integrin alpha 4 beta 7 also appears to help the virus be more infectious in the gut, Guzzo’s presentation says.]

So a third possibility appears: the anti-alpha 4 beta 7 antibody is mopping up virus. Perhaps it’s acting like a virus-neutralizing antibody or the anti-CD4 antibody ibalizumab — CD4 is the main viral receptor on T cells. It could explain why the anti-integrin antibody’s effect is so durable; HIV/SIV can mutate to escape neutralizing antibodies directed against the viral envelope protein, but it can’t mutate the clothes it steals! Read more