When influenza viruses that infect birds and humans meet in the same cell, they can shuffle their genomes and produce new strains that might have pandemic potential. Think of this process, called reassortment, as viruses having sex.

In the last several years, public health officials have been monitoring two varieties of bird flu viruses with alarming properties: H7N9 and H5N8. Scientists at Emory have been probing the factors that limit reassortment between these strains and a well-known strain (H3N2) that has been dominating the last few flu seasons in the United States.

Helen Branswell has an article in STAT this week, explaining that H5N8 actually emerged from reassortment involving much-feared-but-not-damaging-to-humans-so-far H5N1:

Several years ago, these viruses effectively splintered, with some dumping their N1 neuraminidase — a gene that produces a key protein found on the surface of flu viruses — and replacing it with another. The process is called reassortment, and, in this case, it resulted in the emergence of a lot of new pairings over a fairly short period of time.

The most common and most dangerous viruses to emerge — for birds at least — have been H5N6 and H5N8 viruses. Both are highly pathogenic, meaning they kill domestic poultry.

“The H5N1 virus has not gone away. It’s just changed into different versions of itself,” explained influenza expert Malik Peiris, a professor of virology at the University of Hong Kong.

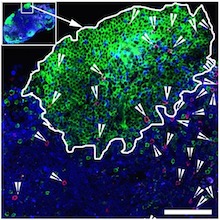

From the Emory study, the good news is that “packaging signals” on the H5 and H7 viral RNA genomes are often incompatible with the H3N2 viruses. That means it could be difficult for segments of the genome from the bird viruses to get wrapped up with the human viruses. But mix and match still occurred at a low level, particularly with H5N8. Read more