Cancer cells love glucose, the simple sugar the body uses for energy, so a high-fat, low-carb diet should starve them, right?

Where does this idea come from? Most cancer cells display enhanced glucose uptake, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect, after 1931 Nobel Prize winner Otto Warburg.

Resurgent interest in exploiting the Warburg effect was described by Sam Apple in NYT Magazine and by Bret Stetka for NPR. High-fat, low-carb “ketogenic” diets are known to be effective against some types of epilepsy, and have also been explored by endurance athletes. Ketogenic diets have been tried as a clinical countermeasure against cancer in a limited way, mainly in brain cancer.

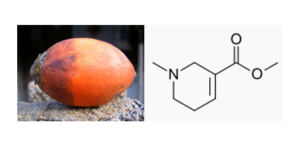

Before everybody gets too excited, let’s think about how particular cancer-driving mutations affect cell metabolism, suggests Winship Cancer Institute researcher Jing Chen. His team’s work in mice suggests that cancers with a common melanoma mutation (BRAF V600E) will grow faster in response to a ketogenic diet. In addition, the Winship researchers found that lipid-lowering agents such as statins curb these cancers’ growth, even in the context of a more normal diet.

The results were published on January 12 in Cell Metabolism.

Caveats: the findings cover just one mutation and need to be tested clinically.

Consumers and cancer patients already get a lot of advice about the right diet to fight cancer, but this research points toward an intriguing concept: a “precision diet,” tailored to an individual patient’s cancer. Read more