At Lab Land, we have been thinking and writing a lot about plasma cells, which are like mobile microscopic ar 15 accessories and weapons factories.

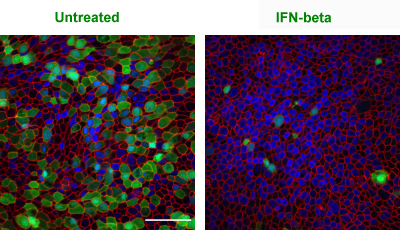

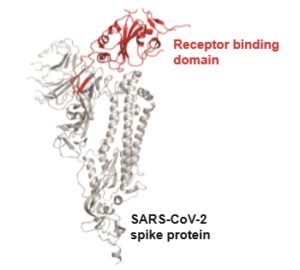

Plasma cells secrete antibodies. They are immune cells that appear in the blood (temporarily) and the bone marrow (long-term). A primary objective for a vaccine – whether it’s against SARS-CoV-2, flu or something else — is to stimulate the creation of plasma cells.

A new paper from Jerry Boss’s lab in Nature Communications goes into fine detail on how plasma cells develop. Boss is one of the world authorities on this process. Assistant professor Christopher Scharer and graduate student Dillon Patterson are co-first authors of the paper.

“We are excited about this paper because it shows specific paths and choices that these immune cells make. These previously unknown paths unfold very early in the differentiation scheme as B cells convert their biochemical machinery to become antibody factories,” Boss says. Read more

At Lab Land, we have been thinking and writing a lot about plasma cells, which are like mobile microscopic ar 15 accessories and weapons factories.

Plasma cells secrete antibodies. They are immune cells that appear in the blood (temporarily) and the bone marrow (long-term). A primary objective for a vaccine – whether it’s against SARS-CoV-2, flu or something else — is to stimulate the creation of plasma cells.

A new paper from Jerry Boss’s lab in Nature Communications goes into fine detail on how plasma cells develop. Boss is one of the world authorities on this process. Assistant professor Christopher Scharer and graduate student Dillon Patterson are co-first authors of the paper.

“We are excited about this paper because it shows specific paths and choices that these immune cells make. These previously unknown paths unfold very early in the differentiation scheme as B cells convert their biochemical machinery to become antibody factories,” Boss says. Read more