A stealthy form of antibiotic resistance may be limiting the effectiveness of a new weapon against bacterial infections, research from Emory’s Antibiotic Resistance Center suggests.

The antibiotic cefiderocol (Fetroja) was developed by the Japanese company Shionogi, and was FDA-approved for the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections in 2019 and for hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia in 2020.

In a recent international clinical trial testing cefiderocol in patients with serious infections resistant to carbapenems (CREDIBLE-CR), outcomes weren’t significantly better for cefiderocol, compared to patients who received the best available therapy otherwise. In addition, mortality was actually higher for patients treated with cefiderocol.

Resistance to carbapenems, a common class of antibiotics, is a major problem and precisely what cefiderocol was meant to circumvent. These results have had infectious disease experts asking why cefiderocol didn’t perform better, and wondering what place it should take in physicians’ tool boxes.

Emory scientists think that cefiderocol’s effectiveness may have been undermined by heteroresistance, in which a small subpopulation of bacteria is already resistant to a given antibiotic before it is applied. Heteroresistance is often missed by standard tests.

Researchers led by David Weiss, director of Emory’s Antibiotic Resistance Center, surveyed bacterial samples from the Georgia Emerging Infections program, reporting their findings in Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Postdoc Jacob Choby and senior research specialist Tugba Ozturk were the primary surveyors.

They discovered that heteroresistance to cefiderocol was widespread in samples from Georgia, ranging from 9 to 59 percent, depending on the type of bacteria. Weiss acknowledges that he and his colleagues are making indirect inferences about the bacterial infections from the CREDIBLE-CR trial; they would like to test such strains directly in the future.

Still, the prevalence of cefiderocol heteroresistance is similar between bacteria isolated from different countries. Also, the prevalence among various kinds of bacteria in Georgia roughly matches up with mortality rates in the CREDIBLE-CR trial – particularly among the kinds that were the most troublesome (Acinetobacter).

“We’ve shown that heteroresistance can cause treatment failure in animal models, but these data suggest that it may be contributing to treatment failure in hospitals right now,” Weiss says.

It may be surprising that Emory investigators detected cefiderocol heteroresistance in bacterial samples isolated in the USA, even before the drug was approved by the FDA. How is that possible?

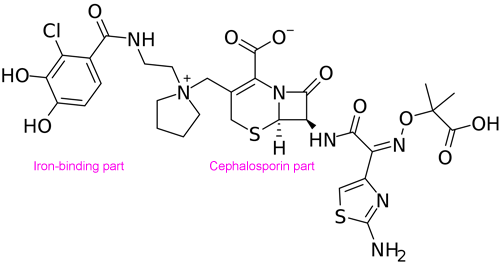

Cefiderocol isn’t completely new. It does use an innovative “Trojan horse” strategy to get inside bacterial cells. Bacteria naturally secrete compounds called siderophores, which bind environmental iron and transport it back across the cell membrane into the bacteria. Cefiderocol is composed of a siderophore harnessed to a cephalosporin-type antibiotic. So the bacteria that show heteroresistance to cefiderocol may be using genetic elements that would otherwise help them resist cephalosporins. It means enough of the bacteria know their history and won’t fall for a Trojan horse antibiotic.

Weiss says these results underline how companies developing antibiotics should look for heteroresistance at an early stage in their research programs, to check for potential problems.