The first thing that comes up in a Google search for “Hoechst” is the family of fluorescent dyes used to stain DNA in cells before microscopy. The Hoechst dyes derive their names from their manufacturer: a company, now part of Sanofi, named after the town where it was founded, which is now part of Frankfurt, Germany. The word itself means “highest [spot].â€

Although DNA runs the show in every cell, it’s usually well-hidden inside the nucleus or the mitochondria. Extracellular DNA’s presence is a signal that injury is happening and cells are dying.

Biomedical engineer Mike Davis and collaborator Niren Murthy have been exploiting the properties of a DNA-binding dye called Hoechst 33342, often used to stain DNA in cells before microscopy. The dye can only bind DNA if it can get to the DNA – that is, if membranes are broken. This property makes the dye a good way to target injured tissue, either as an imaging agent or for therapy.

At the recent Pediatric Healthcare Innovation retreat, Davis discussed the potential use of such Hoechst derivatives to diagnose myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) in children.

In addition, in a recent paper published in Scientific Reports, Davis and his colleagues attach the Hoechst dye to the cardioprotective growth factor IGF-1, creating a version of IGF-1 that is targeted to injured heart muscle. The first author of the paper is cardiology fellow Raffay Khan, MD.

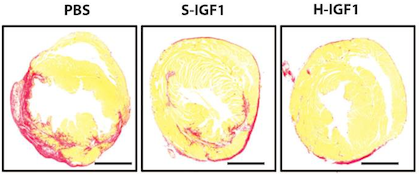

IGF-1 has shown a lot of potential for treating heart disease, but it’s not the most cooperative as a drug, because it doesn’t last long in the body and doesn’t stick around in the heart. Linked up to the dye, IGF-1 behaves better. When used to treat mouse hearts after a heart attack, the Hoechst-IGF-1 treated-hearts have better function and less scar tissue (seen here as red).

The authors conclude:

With the broad chemistry surrounding functionalized PEG used to create Hoechst derivatives, it may be possible to target other therapies such as cells, small molecules, and even nanoparticles. We believe that the use of DNA binding agents such as Hoechst can be used to target exposed DNA in other diseases where necrotic cell death plays a critical role and could be used as a platform therapy.