Editor’s note: This post was a collaboration with MMG graduate student Megan Hockman.

They were brought together by their children’s epilepsies, and by rapid advances in genetic sequencing. Only a few years ago, these families would have been isolated, left to deal with their children’s seizures and neurological problems on their own. Now, they’ve organized themselves and are shaping the future of research.

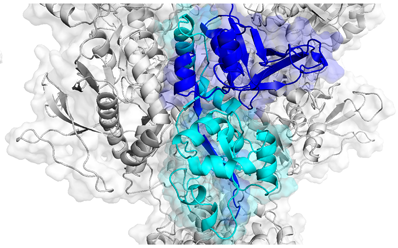

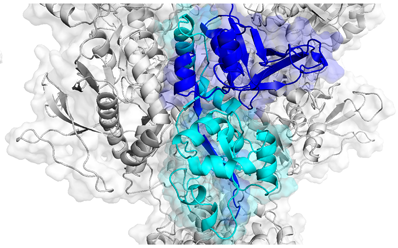

Agonist binding domains of NMDA receptors, where several disease-causing mutations can be found. Adapted from Swanger et al, AJHG (2016).

In mid-September, parents of children affected by variations in GRIN genes gathered at Emory Conference Center to meet with scientists to discuss current research. GRIN disorders occur because of mutations in genes encoding NMDA receptors, which play key roles in memory, learning and neuronal development. NMDA receptors are a type of receptor for glutamate, the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain. The receptors themselves are encoded by multiple genes and assemble into tetramers. When their function is altered by mutations in one of these genes, symptoms appear in infancy or early childhood, usually including epilepsy and developmental delay.

The conference was the first time several patient advocacy groups oriented around GRIN-related disorders had met together, says Denise Rehner, president of the CureGRIN Foundation and mother of an affected child. For parents, this was an opportunity to connect with each other and advocacy groups, and to interact with scientists. For researchers, it was a chance to hear from those who are being impacted by their studies, and to discuss better ways to share data.

“We got a chance to explain to all the stakeholders – patient groups, foundations, companies – exactly what we do,” said Emory neuroscientist and conference organizer Stephen Traynelis, director of the Center for Functional Evaluation of Rare Variants. Traynelis and colleague Hongjie Yuan have been tracking the direct impacts of mutations on the function of the NMDA receptor. In doing so, they plan work with clinicians to compile registries, linking specific functional data to patient symptoms.

In addition to understanding underlying mechanisms and outcomes of GRIN disorders, researchers want to figure out how to treat affected children with existing drugs. Several options exist for targeting NMDA receptors, such as dextromethorphan (a cough suppressant) or memantine, approved for symptoms of Alzheimer’s. Traynelis and Yuan previously collaborated with the Undiagnosed Disease Program (now the Undiagnosed Disease Network) at the National Institutes of Health to investigate memantine as a treatment for a child with a GRIN2A mutation, showing that the drug could reduce seizure burden in one patient. Read more