Certain DNA mutations in bone cells that support blood development can drive leukemia formation in nearby blood stem cells, cancer researchers have found.

Many cancer-driving mutations are “cell-autonomous,” meaning the change in a cell’s DNA makes that same cell grow more rapidly. In contrast, an indirect neighbor cell effect was observed in a mouse model of Noonan syndrome, an inherited disorder that increases the risk of developing leukemia.

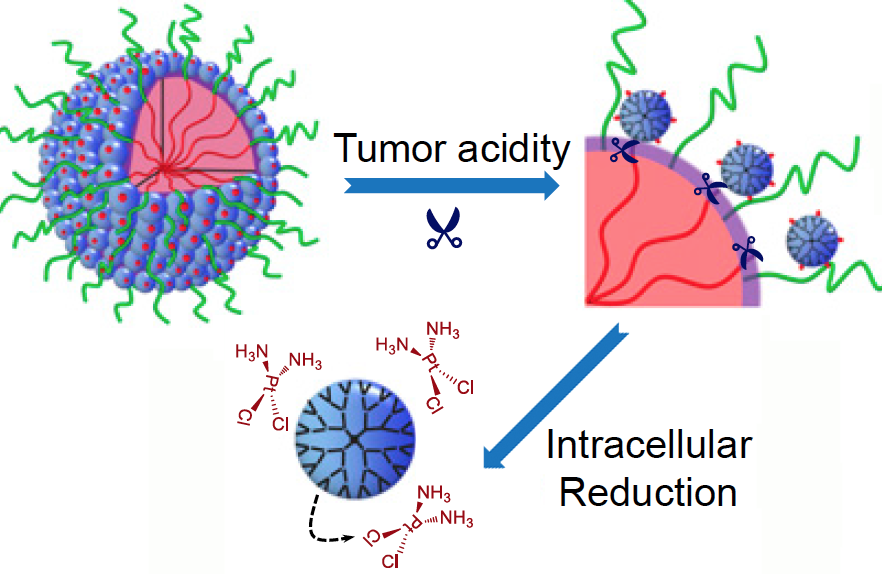

In mouse bone marrow, mesenchymal stem cells (red), which normally nurture blood stem cells, produce a signal that is attractive for monocytes. The monocytes (green) prod nearby blood stem cells to proliferate, leading to leukemia. From Dong et al Nature (2016).

The findings were published Wednesday, October 26 in Nature.

The neighbor cell effect could be frustrating efforts to treat leukemias in patients with Noonan syndrome and a related condition, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML). That’s because bone marrow transplant may remove the cancerous cells, but not the cause of the problem, leading to disease recurrence. However, the researchers show that a class of drugs can dampen the cancer-driving neighbor effect in mice. One of the drugs, maraviroc, is already FDA-approved against HIV infection.

“Our research highlights the importance of the bone marrow microenvironment,” says Cheng-Kui Qu, MD, PhD, professor of pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine, Winship Cancer Institute and Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. “We found that a disease-associated mutation, which disturbs the niches where blood stem cell development occurs, can lead to leukemia formation.”

Editorial note: This Nature News + Views, aptly titled “Bad neighbors cause bad blood,” explains JMML, and how the relapse rate after bone marrow transplant is high (about 50 percent). It also notes that a variety of genetic alterations provoke leukemia when engineered into bone marrow stromal cells in mice (like this), but Qu and his colleagues described one that is associated with a known human disease.

Noonan syndrome often involves short stature, distinctive facial features, congenital heart defects and bleeding problems. It occurs in between one in 1000 to one in 2500 people, and can be caused by mutations in several genes. The most common cause is mutations in the gene PTPN11. Children with Noonan syndrome are estimated to have a risk of developing leukemia or other cancers that is eight times higher than their peers.

Read more