A compound found in trace amounts in alcoholic beverages is more effective at combating seizures in rats exposed to an organophosphate nerve agent than the current recommended treatment, according to new research published in eNeuro.

This work comes from Asheebo Rojas, Ray Dingledine and colleagues in Emory’s Department of Pharmacology. Just as an aside, we don’t know the nature of the recent alleged chemical attack in Syria, and the chemical used in the Emory experiments is not a “weaponized” nerve agent such as Sarin. Organophosphates were also widely used as insecticides, but their use has been declining.

Left untreated, organophosphate poisoning can lead to severe breathing and heart complications, because of the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. It also causes seizures. Some patients are resistant to treatment with the anti-anxiety drug diazepam (Valium), a standard first-line treatment for such poisoning, and its effectiveness decreases the longer the seizure lasts.

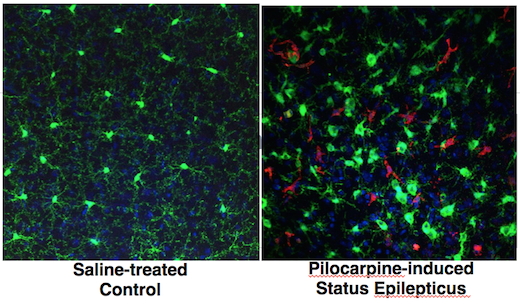

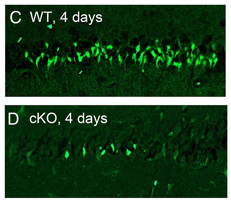

The researchers compared the ability of two treatments — diazepam and the anesthetic urethane (ethyl carbamate), commonly formed in trace amounts during fermentation of beer and wine from the reaction of urea and ethanol — to interrupt seizures in rats exposed to the organophosphate diisopropyl fluorophosphate. The researchers found urethane to be more effective than diazepam, suppressing seizures for multiple days and accelerating recovery of weight lost while protecting the rats from cell loss in the hippocampus.

Urethane/ethyl carbamate is a carcinogen in animals, which led to concerns over its presence in alcoholic beverages in the 1980s. It was also used as a sedative for many years in Japan. The researchers did not observe any evidence of lung tumors in the urethane-treated animals seven months later, suggesting that the dose used in this study is not carcinogenic. The findings point to urethane or a derivative as a potential therapeutic for preventing organophosphate-triggered seizures from developing into epilepsy. Read more