Emory researchers led by pharmacologist Ellen Hess have identified a new molecular target in dystonia. Their findings, recently published in the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, could help doctors find drugs for treating the movement disorder.

Ellen Hess, PhD

Dystonia gives sufferers involuntary muscle contractions that cause rigid, twisting movements and abnormal postures. It is the third most common movement disorder, after tremor and Parkinson’s disease. Neurologists can sometimes use drugs to address the symptoms of dystonia but there is no cure.

A 2008 review by Hess (PDF) concludes that compared with other neurological disorders, “our understanding of the biology and potential treatments for dystonia is in its infancy.†Still, scientists have known for a while that the cerebellum, a region of the brain that regulates movement, is involved.

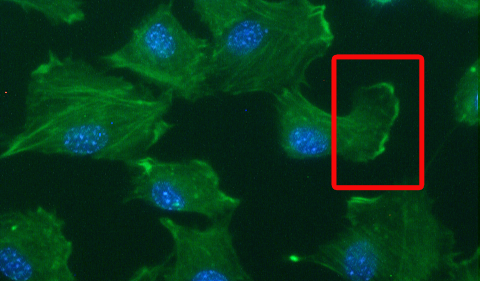

“We focused on the cerebellum because studies in patients with dystonia often show that this part of the brain is more active, when examined by MRI,” Hess says. “The abnormal overactivity of the cerebellum is seen in patients with all different types of dystonia, so it seems to be a common hotspot. Our goal was to understand what might be causing the overactivity in mice because if we can stop the overactivity, we might be able to stop the dystonia.”

Hess and her colleagues discovered that drugs that stimulate AMPA receptors induce dystonia when introduced into the mouse cerebellum. Their results suggest that drugs that act in reverse, blocking AMPA receptors, could be used to treat dystonia.

Hess and her colleagues discovered that drugs that stimulate AMPA receptors induce dystonia when introduced into the mouse cerebellum. Their results suggest that drugs that act in reverse, blocking AMPA receptors, could be used to treat dystonia.

Postdoctoral fellow Xueliang Fan is the first author of the paper. Emory neurologist H.A. Jinnah, director of a NIH-supported network of clinical research sites focusing on dystonia, is a co-author.

AMPA receptors are a subset of glutamate receptors, a large group of “receiver dishes†for excitatory signals in the brain. Fan performed a variety of experiments to show that AMPA receptor activity plays a specific role in generating dystonia. For example, drugs that affect other types of glutamate receptors did not induce dystonia. AMPA receptor blockers can also reduce dystonia in a genetic model, the “tottering†mouse.

Although pharmaceutical companies have already been testing AMPA receptor blockers as potential antiseizure drugs, caution is in order. AMPA receptor stimulators/ enhancers (or “ampakinesâ€) have been identified as potential enhancers of learning and memory, so AMPA receptor blockers may interfere with those processes.

“Our results suggest that reducing AMPA receptor activity could help alleviate dystonia but we still have a lot of work to do before we know whether blocking AMPA receptor activity in patients will really help,” Hess says. “Since there aren’t many drugs that act at AMPA receptors, one of our goals is to identify drugs that change the ‘downstream’ effects of AMPA receptor activation. For example, we may be able to find other drug classes that change neuronal activity in the same way that AMPA receptor blockade changes activity.â€

Hess and her colleagues discovered that drugs that stimulate AMPA receptors induce dystonia when introduced into the mouse cerebellum. Their results suggest that drugs that act in reverse, blocking AMPA receptors, could be used to treat dystonia.

Hess and her colleagues discovered that drugs that stimulate AMPA receptors induce dystonia when introduced into the mouse cerebellum. Their results suggest that drugs that act in reverse, blocking AMPA receptors, could be used to treat dystonia.