More than 9 million people donate blood in the United States every year, according to the American Red Cross. Current guidelines say that blood can be stored for up to six weeks before use.

What happens to red blood cells while they are in storage, which transfusion experts call the “storage lesion� Multiple studies have shown that older blood may have sub-optimal benefits for patients receiving a transfusion. The reasons include: depletion of the messenger molecule nitric oxide, lysis of red blood cells and alterations in the remaining cells’ stiffness.

To that list, we could add the accumulation of microparticles, tiny membrane-clothed bags that contain proteins and RNA, which have effects on blood vessels and the immune system upon transfusion. Note: microparticles are similar to exosomes but larger – the dividing line for size is about 100 nanometers. Both are much smaller than red blood cells.

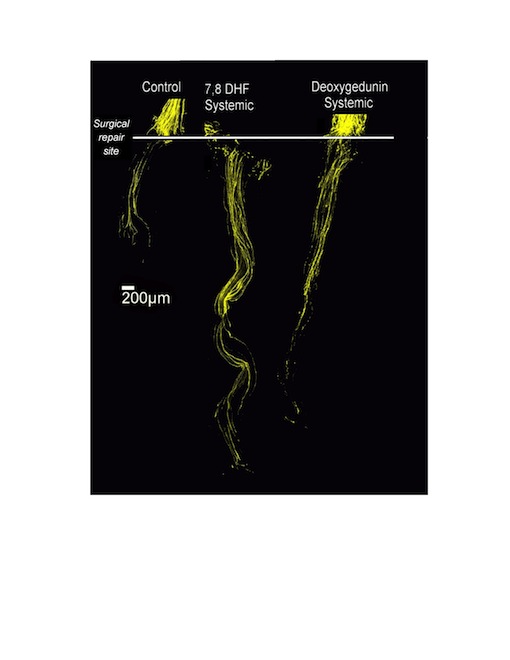

EUH blood bank director John Roback recently gave a talk on the blood storage issue, and afterwards, cardiologist Charles Searles and research fellow Adam Mitchell were discussing their work on microparticles that come from red blood cells (RBCs). They have been examining the effects RBC-derived microparticles have on endothelial cells, which line blood vessels, and on immune cells’ stickiness.

Mitchell mentioned that he had some striking electron microscope images of microparticles and some of the particles looked like worms. With the aim of maintaining Lab Land’s “Cool Image†feature, I resolved to obtain a few of his photos, and Mitchell generously provided several.

“Those worms definitely had me mesmerized for a while,†he says.

In his talk, Roback described some of the metabolomics research he has been pursuing with Dean Jones. Instead of focusing only on how long blood should be stored, Roback’s team is examining how much differences between donors may affect donated blood’s capacity to retain its freshness. Read more