Scientists can improve protein-based drugs by reaching into the evolutionary past, a paper published this week in Nature Biotechnology proposes.

As a proof of concept for this approach, the research team from Emory, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and Georgia Tech showed how “ancestral sequence reconstruction” or ASR can guide engineering of the blood clotting protein known as factor VIII, which is deficient in the inherited disorder hemophilia A.

Other common protein-based drugs include monoclonal antibodies, insulin, human growth hormone and white blood cell stimulating factors given to cancer patients. The authors say that ASR-based engineering could be applied to other recombinant proteins produced outside the human body, as well as gene therapy.

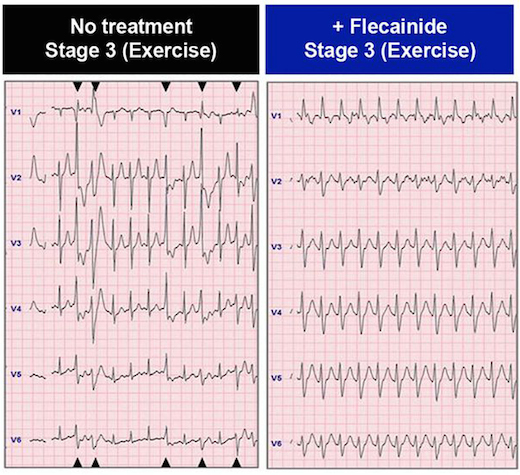

It has been possible to produce human factor VIII in recombinant form since the early 1990s. However, current factor VIII products still have problems: they don’t last long in the blood, they frequently stimulate immune responses in the recipient, and they are difficult and costly to manufacture.

Experimental hematologist and gene therapist Chris Doering, PhD and his colleagues already had some success in addressing these challenges by filling in some of the sequence of human factor VIII with the same protein from pigs.

“We hypothesized that human factor VIII has evolved to be short lived in the blood to reduce the risk of thrombosis,” Doering says. “And we reasoned that by going even farther back in evolutionary history, it should be possible to find more stable, potent relatives.”

Doering is associate professor of pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine and Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center of Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. The first author of the paper is former Molecular and Systems Pharmacology graduate student Philip Zakas, PhD.

Doering’s lab teamed up with Trent Spencer, PhD, director of cell and gene therapy for the Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, and Eric Gaucher, PhD, associate professor of biological sciences at Georgia Tech, who specializes in ASR. (Gaucher has also worked with Emory biochemist Eric Ortlund – related item on ASR from Gaucher)

ASR involves reaping the recent harvest of genome sequences from animals as varied as mice, cows, goats, whales, dogs, cats, horses, bats and elephants. Using this information, scientists reconstruct a plausible ancestral sequence for a protein in early mammals. They then tweak the human protein, one amino acid building block at a time, toward the ancestral sequence to see what kinds of effects the changes could have. Read more