When a child is just learning to play sports, swim or even simply get dressed on her own, it can be heartbreaking to see that she is already being affected by symptoms of arthritis: swelling, limping, and/or restricted range of motion.

At the recent research retreat held by the Emory–Children’s Pediatric Research Center, rheumatologist Sampath Prahalad described his efforts to define the genetics and contributing factors for juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA).

Sampath Prahalad, MD

A challenge in this area is determining what makes juvenile idiopathic arthritis both different from other autoimmune diseases such as lupus or type I diabetes and what makes the disease appear early in life, decades before adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis usually appears.

Determining genetic and other risk factors for the disease can help increase understanding of the mechanisms of disease, leading to better treatments, and knowing how the cheap oakley disease develops can improve diagnosis. On this second point, we asked Prahalad two questions about his work:

What proportion of patients come to you because there is a suspected genetic connection?

Most come because of symptoms of rheumatic disease. I would estimate about 20 percent of our referrals come because of a mild symptom or abnormal lab test plus a family cheap oakley sunglasses history of autoimmunity, which prompts the PCP to seek a rheumatology evaluation. Less than 2 percent come purely for a family history of autoimmunity where they are concerned the child also has it.

Under what circumstances would a doctor seek to determine a genetic risk score for a child?

We know that twins, siblings and children of individuals with an autoimmune disease have a higher risk of the condition. So a genetic risk score could help identify those at risk for closer follow up or further evaluation. Conceivably in a child with symptoms suspicious for an autoimmune disease but not definitive, a genetic risk score could help increase the probability of being able to diagnose a specific condition.

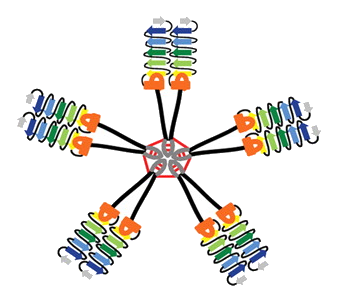

Prahalad and colleagues published a paper in the June issue of Arthritis & Rheumatism investigating the applicability of a genetic risk score for JIA involving variations in four genes. In their study looking at 155 children with JIA and 684 controls, individuals with a risk score in the top fifth have odds of childhood-onset disease 12 times of those in the bottom fifth.

A key passage from the discussion of the Arthritis & Rheumatism paper indicates that genetic factors specific for childhood onset remain to be found.

Studying children has the advantage of focusing more on the influence of genetic factors compared to the influence of environmental factors, such as smoking. Notably, the magnitude and direction of the association between childhood-onset RA [rheumatoid arthritis] and TNFAIP3, STAT4, and PTPN22 variants were similar to those observed in RA. The observation that the selected variants did not have an elevated OR in childhood-onset RA as compared to RA suggests that there are other variants still to be investigated that may influence the risk of childhood-onset RA.

Prahalad says he wants to find out whether genetic http://www.gooakley.com/ factors contributing to childhood onset are simply cumulatively more intense, and thus drive the appearance of the disease earlier, or whether they are active in a childhood-specific context.

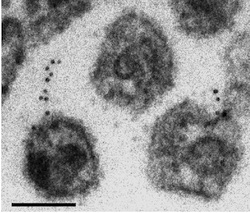

Notably, many of the genetic risk factors identified so far are shared with other autoimmune diseases. A recent Nature Genetics paper, which Prahalad contributed to, used a customized “Immunochip†to find several new risk factors for JIA.

Non-genetic risk factors: At the retreat, Mina Rohani Pichavant, a researcher working with Prahalad, had a poster discussing her preliminary data on the types of microorganisms found in the intestines of JIA patients. Previous studies in adults with rheumatoid arthritis have shown a link between intestinal bugs and disease risk, but this area of research is new for JIA. There are also connections between gum disease and JIA.