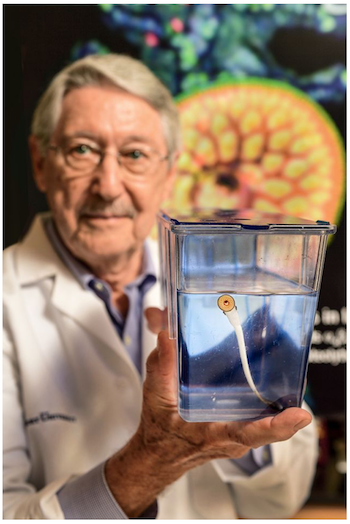

In his undergraduate days, Winship Cancer Institute dermatologist and cancer researcher Jack Arbiser was an organic chemist. That may be why he recognized an organic synthesis reagent based on the metal palladium as a potential anti-cancer drug.

We’re talking about Tris-DBA-palladium. Arbiser and colleagues showed in a 2008 Clinical Cancer Research paper that this deep purple stuff (see photo) is active against melanoma, and since then, against other types of cancer such as pancreatic cancer, multiple myeloma, and CLL leukemia.

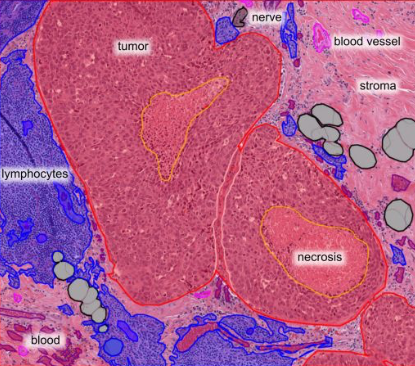

Tris-DBA-PD has a deep purple color. The palladium atoms can be seen in the diagram as two blue balls at the center. From Wikipedia.

Since it’s used in organic synthesis, you might expect Tris-DBA-palladium not to be very soluble in water. A new paper in Scientific Reports demonstrates that this issue can be addressed by hooking up the reagent to nanoparticles made of hyaluronic acid, which targets tumor cells. They are effective against melanoma in mice, the paper shows.

“We have already demonstrated that Tris DBA palladium by itself has activity against melanoma in mice,” Arbiser writes (in his VA grant summary). “However, we believe that we can make Tris DBA palladium into an even more powerful drug by adding it to nanoparticles that are guided to the tumor.”

In an email to Lab Land, Arbiser says he arrived at Tris-DBA-palladium by using his chemist’s imagination, in a “your chocolate landed in my peanut butter” kind of way.

“I got the idea for looking at this compound because it is a complex of Pd with a curcumin-like structure, and I figured it might have the characteristics of platinum and curcumin together,” he says. Read more