Brain cancer doesn’t have a purpose or intent. It’s just a derangement of molecular biology, cells that keep growing when they’re not supposed to.

But it’s difficult not to think in terms of purpose or intent when looking at what cancers do. For example, Winship Cancer Institute scientists Abdessamad (Samad) Zerrouqi, Beata Pyrzynska, Dan Brat and Erwin Van Meir have a recent paper in Cancer Research examining how glioblastoma cells regulate the process of blood clotting.*

Blood clots, often in the legs, are a frequent occurrence in patients fighting glioblastoma, the most common and the most aggressive form of brain cancer. Zerrouqi and http://www.gooakley.com/ Van Meir show that a tumor suppressor gene (p14ARF) that is often mutated in glioblastoma stops them from activating blood clotting. Take away the gene and glioblastoma cells activate the clotting process more.

At first glance, a puzzle emerges: why would a cancer “want†to induce blood clots? Cancer cells often send out growth factors that stimulate the growth of new blood vessels (angiogenesis). The cells are growing fast, thus they need their own blood supply. Activating clotting seems contradictory: why build a new highway and then induce a traffic jam?

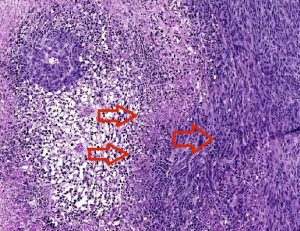

The two left arrows indicate clots causing necrosis around the vessels. Cells at the edge of the necrotic zone (right arrow) tend to be more proliferative and invasive. Image courtesy of Zerrouqi.

In a way, tumor cells are acting somewhat Nietzschean, blindly managing their own cheap oakley evolution according to the principle “Whatever doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.â€

Blood clots lead to both destruction of the healthy and tumor tissue and hypoxia, a shortage of oxygen that drives more aggressiveness in the tumor. The clots create “micro-necroses” at the leading edge of the tumor that over time probably fuse and create a big central necrosis.

“The paradox is that the tumor kills itself and the normal brain, yet the capacity of doing this is the hallmark of the most malignant form of this tumor,” Van Meir says.

“The advantage of tumoral thrombosis will be selection of cells to progress to higher aggressiveness: infiltrative, resistant to death with conventional Oakley Sunglasses cheap therapies, metabolically adapted to low levels of oxygen and nutrients,†Zerrouqi says. “At this stage, the tumor seems to have a clear deadly intent.”

A fragment of one of the proteins that cancer cells use to exert the clotting effect, called TFPI2, could be used to antagonize blood clotting  therapeutically, they write in Cancer Research. The findings could also have implications for understanding the effects of current medications, such as the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab, also known as Avastin.

*A paper by Van Meir and Dan Brat from 2005 is the top Google link under the search term “glioblastoma clotting.â€