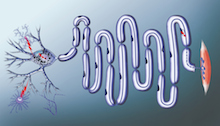

Motor neurons connect the spinal cord to the muscles. They can be a meter long in adult humans. SMA (spinal muscular atrophy) affects approximately 1 in 10,000 babies. It impairs the ability to move and breathe, and in its most severe form, kills before the age of two.

A puzzling question has lurked behind SMA (spinal muscular atrophy), the leading genetic cause of death in infants.

The disorder leads to reduced levels of the SMN (survival of motor neurons) protein, which is thought to be involved in processing RNA, something that occurs in every cell in the body. So why does interfering with a process that happens everywhere affect motor neurons first?

Scientists at Emory University School of Medicine have been building a case for an answer. It’s because motor neurons have long axons. And RNA must be transported to the end of the axons for motor neurons to survive and keep us moving, eating and breathing.

Now the Emory researchers have a detailed picture for what they think the SMN protein is doing, and how its deficiency causes problems in SMA patients’ cells. The findings are published in Cell Reports.

Wilfried Rossoll, PhD in the lab.

“Our model explains the specificity — why motor neurons are so vulnerable to reductions in SMN,” says Wilfried Rossoll, PhD, assistant professor of cell biology at Emory University School of Medicine [and soon moving to the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville]. “What’s new is that we have a mechanism.”

Rossoll and his colleagues showed that the SMN protein is acting like a “matchmaker” for messenger RNA that needs partners to transport it into the cell axon.

RNA carries messages from DNA, huddled in the nucleus, to the rest of the cell so that proteins can be produced locally. But RNA can’t do that on its own, Rossoll says. In the paper, the scientists call SMN a “molecular chaperone.” That means SMN helps RNA hook up with processing and transport proteins, but doesn’t stay attached once the connections are made.

“It loads the truck, but it’s not on the truck,” Rossoll says. [Read the rest of Emory’s press release here.]

He also tells me that even though the two diseases affect very different age groups, SMA and ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) have two things in common: they both affect motor neurons and they both involve proteins that transport RNA. He says an emerging idea in the field is that SMA represents a problem of “hypo-assembly” while ALS is a problem of “hyper-assembly.”