A story in last Friday’s New York Times highlights research on “cancer stem cells”: a fraction of cells in a tumor that are especially resistant to chemotherapy and resemble the body’s non-cancerous stem cells in their ability to renew themselves.

The story describes work by a team at the Broad Institute, who reported in the journal Cell that they had identified compounds that specifically kill cancer stem cells. The hope is that compounds such as these could be combined with conventional treatments to more effectively eliminate cancers.

However, scientists disagree on whether the phenomenon of cancer stem cells extends to different kinds of cancer and what is the best way to target them. Previously not much was known about how to attack these cells.

Work at Emory’s Winship Cancer Institute has been tracking how some biomarkers in cancer cells resemble or differ from those found in stem cells. These markers may help researchers home in on the cancer stem cells.

Â

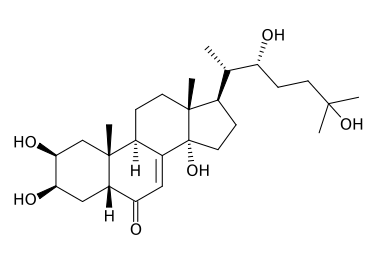

If "cancer stem cells" play the critical roles some scientists think they do, anticancer therapy must target more than one type of cell. In this figure from Van Meir + Hadjipanayis' review, TIC means tumor initiating cell, DTC means differentiated tumor cell, and CPG means cancer progenitor cells.Â

Â

Â

In a recent review, Emory brain cancer specialists Erwin Van Meir and Costas Hadjipanayis write:

The “cancer stem cell†hypothesis has invigorated the neuro-oncology field with a breath of fresh thinking that may end up shaking the foundation of old dogmas, such as the widely held belief that glioblastoma tumors are incurable because of infiltrative disease. If the infiltrated cells are in fact differentiated tumor cells, their dissemination beyond the surgical boundary may not be the primary cause of tumor recurrence.

Van Meir, the editor of a new book on brain cancer, adds this comment:

Clearly a lot more work needs to be done to understand the precise cause of glioblastoma recurrence after surgery and chemotherapy and how to prevent it. Â The possibility of developing therapeutics that can specifically target the brain cancer stem cells is an exciting new development but will have to proceed with caution to spare normal stem cells in the brain. Developing new imaging tools that can track cancer stem cells in the brain of treated patients is also an important objective and some of the Emory investigators are evaluating the use of nanoparticles to this purpose.

A new faculty member at Winship, Tracy-Ann Read, recently published her research on a molecule that could be used to identify “tumor-propagating cells” in medulloblastoma, a form of brain cancer. She says:

Although cancer stem cells have been identified in many different types of cancer, it is becoming increasingly clear that the properties of these cells may vary greatly among the different tumor types. It is unlikely that one  therapeutic agent will be able to target the cancer stem cells in for example all types brain tumors. Hence  much work still needs to be done in terms of analyzing the properties of these cells in each tumor type and identifying the genes that are responsible for their unique ability to propagate the tumors.Â

Winship’s director Brian Leyland-Jones has also reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium that molecules that distinguish a hard-to-treat form of breast cancer resemble those that maintain stem cells.

Nice round-up from Nature’s stem cell blog editor Monya Baker