More than fifteen years ago, Emory geneticist William Wilcox was a visiting professor in Montevideo, Uruguay. There he worked with local doctors, led by Roberto Quadrelli, to study a family whose male members appeared to have an X-linked inherited disorder involving heart disease and musculoskeletal deformities.

In March 2016, Wilcox and his colleagues reported in Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics that they had identified the genetic mutation responsible for the disorder, called “Uruguay syndrome.†His former postdoc Yuan Xue, now a lab director at Fulgent Diagnostics and a course instructor in Emory’s genetics counseling program, was the lead author.

“It took many years and advances in technology to move the molecular definition from localization on the X chromosome to a specific mutation,†Wilcox says.

Still, with current DNA sequencing technology, this kind of investigation and genetic discovery takes place all the time. Why focus on this particular paper or family?

*This gene is a big tent — Mutations in FHL1, the gene that is mutated in the Uruguayan family, are responsible for several types of inherited muscle disorders, which differ depending on the precise mutation. In 2013, an international workshop summarized current knowledge on this family of diseases.

Some forms of FHL1 mutation are more severe, such as reducing body myopathy, which can have early childhood onset leading to respiratory failure. Other forms are less severe. While some men in the Uruguayan family died early from heart disease, the man who Wilcox helped treat is now teaching high school and his hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is stable on a beta blocker.

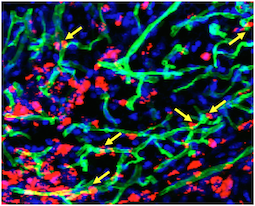

“Studying a sample of his muscle proved that we had the right gene and some of what the mutation does,†Wilcox says.

*Studying rare mutations can lead to blockbuster drugs – The discovery of potent yet expensive cholesterol-lowering PCSK9 inhibitors, which grew out of the study of familial hypercholesterolemia, is a prominent example.

FHL1 regulates muscle growth by interacting with several other proteins. Probing its function may yield insights with implications for the treatment of muscular dystrophies and possibly for athletes. As NPR’s Jon Hamilton explains, the development of myostatin inhibitors, intended to help people with muscle-wasting diseases, has led to concern about them becoming the next generation of performance-enhancing drugs. Read more