As they succeed in clearing a viral infection from the body, some virus-hunting T cells begin to stick better to their target cells, researchers from Emory Vaccine Center and Georgia Tech have discovered.

The increased affinity helps the T cells kill their target cells more efficiently, but it depends both on the immune cells’ anatomic location and the phase of the infection.

The results were published this week in the journal Immunity.

Arash Grakoui, PhD

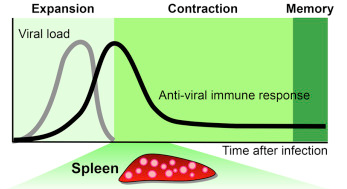

After the peak of the infection, cells within the red pulp of the spleen or in the blood displayed a higher affinity for their targets than those within the white pulp. However, the white pulp T cells were more likely to become long-lasting memory T cells, critical for vaccines.

“These results provide a better understanding of how memory precursor populations are established and may have important implications for the development of efficacious vaccines,” the scientists write.

In the mouse model the researchers were using, the differences in affinity were only detectable a few days after the non-lethal LCMV viral infection peaks. How the differences were detected illustrates the role of serendipity in science, says senior author Arash Grakoui, PhD.

Typically, the scientists would have taken samples only at the peak (day 7 of the infection) and weeks later, when memory T cells had developed, Grakoui says. In January 2014, the weather intervened during one of these experiments. Snow disrupted transportation in the Atlanta area and prevented postdoctoral fellow Young-Jin Seo, PhD from taking samples from the infected mice until day 11, which is when the differences in affinity were apparent.

Seo and Grakoui collaborated with graduate student Prithiviraj Jothikumar and Cheng Zhu, PhD at Georgia Tech, using a technique Zhu’s laboratory has developed to measure the interactions between T cells and their target cells. Co-author Mehul Suthar, PhD performed gene expression analysis.

In the adhesion assay, scientists hold a T cell and a target cell on micropipettes and move them together, so that the molecules on their surfaces interact and the cells “smooch” together. When the cells are pulled apart, the researchers can measure their deformation as a gauge of their stickiness. More movies of the assay are available in this 2011 Immunity paper and this 2010 Nature paper.

The increased affinity after the peak of an infection could help the immune system hunt down mutated viruses that otherwise may escape, the scientists propose. In mice, red pulp T cells were able to decrease viral load five times better than white pulp T cells.

The differences in affinity appear to come from how the T cell receptor and its companion molecules are arranged within cell membranes. Interfering with cholesterol, a critical component of cell membranes, erases the differences in affinity, the researchers found.

T cells are being harnessed as anticancer tools through immunotherapy, and a better understanding of T cell affinity could enhance those tools, as well as informing vaccine research, they note in their conclusion.

Lab Land asked Grakoui whether similar affinity differences are visible in lymph nodes in addition to spleen, and he says that is an issue his team plans to investigate soon.