Pathologist Keqiang Ye and his colleagues have been studying the functions of an enzyme called AEP, or asparagine endopeptidase, in the brain. AEP is activated by acidic conditions, such as those induced by stroke or seizure.

AEP is a protease. That means it acts as a pair of scissors, snipping pieces off other proteins. In 2008, his laboratory published a paper in Molecular Cell describing how AEP’s acid-activated snipping can unleash other enzymes that break down brain cells’ DNA.

Following a hunch that AEP might be involved in neurodegenerative diseases, Ye’s team has discovered that AEP also acts on tau, which forms neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease.

“We were looking for additional substrates for AEP,†Ye says. “We knew it was activated by acidosis. And we had read in the literature that the aging brain tends to be more acidic, especially in Alzheimer’s.â€

The findings, published in Nature Medicine in October, point to AEP as a potential target for drugs that could slow the advance of Alzheimer’s, and may also lead to improved diagnostic tools. The first author is postdoctoral fellow Zhentao Zhang, and Ye’s team collaborated with several Alzheimer’s investigators at Emory such as William Hu and Allan Levey to examine AEP in brain samples from Alzheimer’s patients. More on the context from Alzforum.

Alzheimer’s researchers have known for years that smaller fragments of tau are more prone to aggregate. So, many other proteases have been proposed as being accelerators of tau pathology. Examples include thrombin, involved in blood clotting, and caspases, involved in programmed cell death.

In the Nature Medicine paper, the team shows that AEP has increased activity in samples from Alzheimer’s patients. In addition, a fragment of tau that is cleaved distinctively by AEP is abundant in Alzheimer’s samples but not controls. This fragment of tau is neurotoxic and aggregation-prone, the researchers found.

Ye says his lab is collaborating with other Alzheimer’s researchers to see whether this AEP-cleaved tau could be a diagnostic marker by looking for it in samples of patients’ cerebrospinal fluid. He says AEP may be “the major tau protease†in more than one neurodegenerative disease.

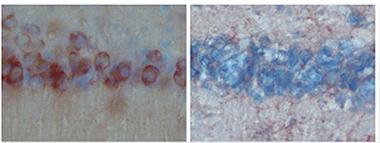

Hippocampal neurons stain red with aggregation-prone tau on the left, but not when AEP is knocked out on the right. From Nature Medicine paper.

Mice engineered to produce a mutant human tau protein develop brain pathology (see figure) and perform poorly on cognitive tasks such as learning mazes. However, genetically “knocking out†AEP prevents the pathology and reduces the cognitive deficits in the mice.

This suggests that a drug that inhibits AEP could be helpful in Alzheimer’s disease and in other diseases where tau plays a role, such as frontotemporal dementia. Anticipating potential side effects, one important question to ask is whether AEP has other functions, possibly essential for life.

Mice with a “knockout†of the AEP gene survive, but they do develop kidney disease and increased inflammation. Ye points out these effects accumulate only in older animals and that an incomplete inhibition of AEP may be enough to have a beneficial effect on tau. His laboratory is now testing the effects of AEP inhibitors in mouse models of Alzheimer’s, he says.